The phrase “we are all treaty people” effectively expresses the legal obligations that all Canadians have to uphold the terms of the treaties. And to ensure that they are not breaking the contract, Canadians must educate themselves about their obligations and responsibilities to Indigenous nations and the land.

Taylor MacLean, Centre for Indigenous Studies, University of Toronto

If you want to understand the historical contexts of treaties in Canada and their ongoing impact on all of us – Indigenous and nonindigenous – it is essential to know how our histories have been recorded.

This article is the first in a series delving into the kinds of research historians undertake to support Indigenous land claims in Canada. In upcoming posts, we’ll share more about archival and sociocultural research and GIS mapping. But written documents are only one source of information for land claims reports; they can be insufficient, incomplete, or occasionally misleading when reconstructing treaty histories. As researchers, we also value the lived experience and traditional knowledge of Indigenous communities and cultural memory keepers as reflected through family genealogies and oral histories. Provincial and federal courts increasingly recognize these essential resources.

Archives: Hidden Treasures

There are more than 700 archives in Canada, ranging from private and corporate collections to university archives and municipal, provincial, territorial, and national institutions. Their agendas may vary, but most are focused on the care, access, preservation, and validation of heritage materials.

Archival documents are at the heart of expert historical reports for land claims. Historians analyze newspaper accounts, journals, letters, field notes, departmental reports, orders in council, demographic statistics, paylists, and more. But most archival collections have yet to be digitized. In fact, online resources represent a tiny percentage of the documents you’ll need to review for any study of treaties in Canada. Bottom line: if you’re undertaking substantive archival research, you must travel.

You will also have to sharpen your detective skills because the ‘finding aids’ describing archival collections vary in quality and content. It’s true that many archival institutions and professionals are committed to creating new vocabularies and ontologies for metadata, collaborating as much as possible to ensure that descriptions of Indigenous and other materials are accessible and culturally relevant. However, Indigenous languages are rarely included in catalogue records; place names change over time, and Indigenous people’s names may be adapted or spelled in various ways in official government documents or omitted entirely. Some archives don’t prioritize Indigenous materials or reconciliation. And it’s no surprise to anyone managing any file system anywhere that occasionally, documents get misplaced or misfiled.

Treaty histories are disruptive.

Once you find the necessary documents and begin to weave together timelines and narratives, the content you encounter may be mundane and factual – but it can also be deeply unsettling.

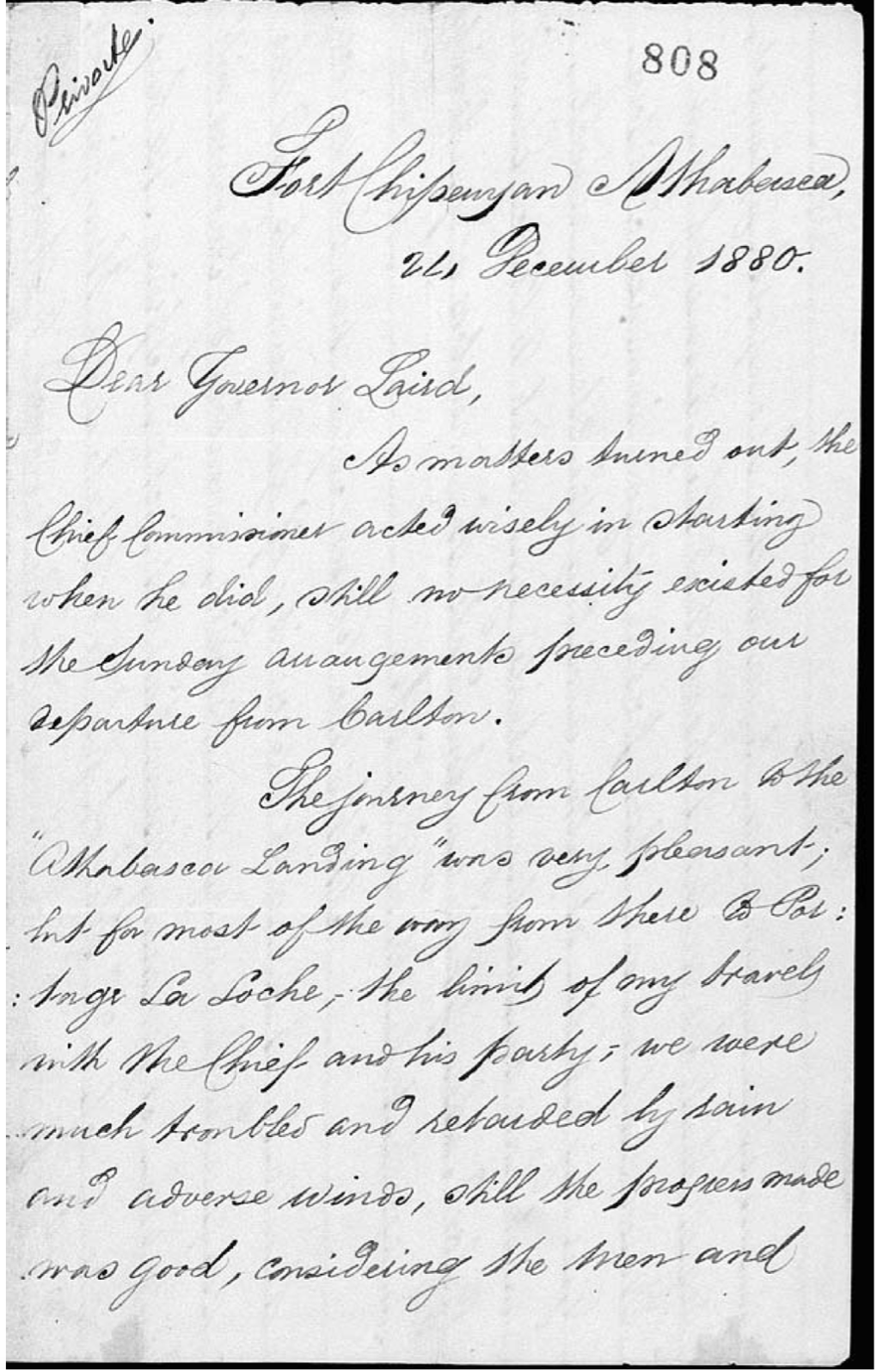

Take, for example, an excerpt from a letter written by Roderick MacFarlane, Chief Factor, Fort Chipewyan, to David Laird, Lieutenant Governor of the Northwest Territories, on December 4, 1880. As documented by Library and Archives Canada, MacFarlane critiqued the federal government for its lack of concern about destitute Indigenous Nations in what is now northern Alberta: “Despite such persistent pleas for help, the government continued with its policy of no-treaty-no-help for another 19 years. The government’s change of heart coincided with the discovery of gold in the Yukon.”

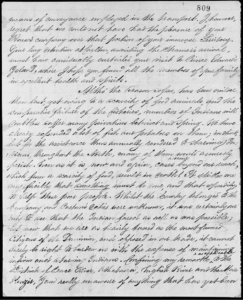

Here’s a partial transcription for the letters below:

“… owing to the scarcity of food animals, and the comparative failure of the fisheries, numbers of Indians will doubtless suffer many privations betwixt [now] and Spring. We have already expended a lot of fish and potatoes on them; in short, but for the assistance thus annually rendered to starving Indians throughout the North, many of them would assuredly perish… It strikes me very forcibly that something must be done and that speedily to help these poor people. Confining my remarks as applicable to the District of Peace River, Athabasca, English River, and the Mackenzie, I am really unaware of anything that has yet been accomplished by our rulers … since the territory was transferred to Canada.”

Ref. No.: MG29, A11, vol. 1, pp. 808-809

At Inclusiv Heritage, we locate, digitize, transcribe, manage, and evaluate documents like these as part of our support for legal teams and Indigenous Nations. Other services we provide are environmental/culture mapping, GIS research, and workshops tailored for community and corporate sustainability.

Upcoming blogs will focus on archival reconciliation and relationship building, the essential role of traditional knowledge and oral histories in land claims, and Indigenous data sovereignty.

We look forward to hearing from you about ideas you want to know about and how we can help support your organization!